The Litigious History of the Evansville Seminary

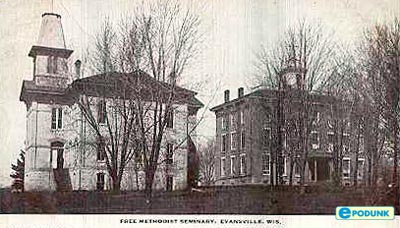

The response to Wally’s post on Almeron Eager’s will and its effect on the pending library expansion showed that our readership digs Evansville history, so let’s keep the ball rolling. This story involves many of Evansville’s founding fathers and one of the most historic landmarks in town, the Evansville Seminary.

The story begins in 1855 with David L. Mills, a local attorney who owned the land the Seminary currently sits on (yes, the very same David L. Mills who ran a notoriously nasty campaign for state assembly against our town’s namesake, Dr. John M. Evans, in 1872) . He gathered 13 of the most prominent people in Evansville and the group began planning and constructing the Evansville Seminary after Mills gifted the land to the new school. The school started holding classes in 1857 while the campus was still under construction.

The school struggled with debt throughout the 1860s and 1870s, which caused control of the school to be transferred from the Methodists to the Free Will Baptists. Unsurprisingly, the school started receiving less money from the Methodists–Mills accused the local Methodists of “prosecuting an unprovoked and unholy war on the Seminary”–and the school continued its financial free fall.

When it became clear that no religious denomination wanted to take over the failing school, some of the Seminary’s stockholders voted to sell the school to a new shoe company, the Evansville Boot & Shoe Company (conveniently, some of those voting on the sale also owned shares in the new shoe company, as did Almeron Eager). Mills, in two words, flipped out. He claimed that as part of his transfer of the land, the Seminary agreed that the property would revert back to him if it were ever used for something other than a school. And these are exactly the right ingredients to create six years of litigation.

Mills’s first problem was that the property’s deed did not contain a clause stating that the Seminary would return to him if it ever ceased being a school. The case made its first trip to the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 1879 with John R. Bennett and future U.S. Representative John Winans representing Mills and Burr W. Jones (who, among other things, became a U.S. Representative, a Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice, and had the road going around the upper diamond named after him) representing the Seminary. The Court held that it could write the new clause into the deed, but that it did not have the power to force the Seminary to give the land back to Mills because Mills had not filed the correct type of legal claim.

Undeterred, Mills re-filed and two years later the case again made it up to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. And again, the Court said it could not force the transfer back to Mills because he had not filed the correct legal claim (perhaps this was not his attorneys’ finest hour).

Still undeterred, Mills brought suit again and the Wisconsin Supreme Court again heard the case in 1883. The parties argued over whether it was appropriate to amend the deed based on oral agreements, but the Court undercut them both. According to the Court, even if the clause existed, the Seminary would not revert to Mills until the building was actually used as something other than a school. The Court took issue with the fact that the transfer to the new shoe company was only voted on by a minority of the Seminary stockholders and that the shoe company had never actually used the property. So, the Court reasoned, it didn’t matter what the deed’s terms were because the property had never ceased being a school. After half of decade of litigation, the Seminary remained in business–and whatever happened to the Evansville Boot & Shoe Company appears lost to history.

Many thanks go to Ruth Ann Montgomery for her excellent research on this topic, which provided much of the background for this post. You can read her entire history of the Evansville Seminary here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!